This Article was written by David John Tattersfield.

The first day of July, 1916 was a day like no other in the history of the British Army, with 60,000 casualties being incurred on this day; of these 20,000 were fatal. Whilst no-one with the surname Tattersfield was killed on this day, the family did not escape unscathed.

Malcolm Bruce Paterson was the son of Malcolm McCulloch Paterson and Constance Paterson (nee Tattersfield). Constance Tattersfield was born 16 Oct 1853, the third child of George Tattersfield, blanket manufacturer of Ravensthorpe, and Hannah nee Walker. An account of George’s life is given in the Section “Tattersfield Families in England” on this Website.

Malcolm was the youngest of four, and was born in Shipley (or North Bierley), near Bradford in the third quarter of 1893. It is likely that the family were well-off; from the 1901 Census it is recorded that they had a housemaid, and an Irish cook. The father, Malcolm McCulloch Paterson was about 13 years older than the mother Constance (nee Tattersfield). He was a civil engineer, and one of Malcolm’s older brothers was a mechanical engineer apprentice.

Unfortunately, we know little of Malcolm’s early life. In the Census of 1901 he was a 7-year old with his parents at West Point, Shipley, Bradford. In the 1911 Census he was a Farm Pupil, boarding with a farmer, Christopher Leadley, near Scarborough, on the east coast of Yorkshire. In 1914 he was an agricultural student. We can surmise that, like many others of his generation, he was highly patriotic.

At the outbreak of the Great War, in August 1914, it was confidently announced that it would be a short war – in fact it would be all over by Christmas. Not many people thought otherwise.

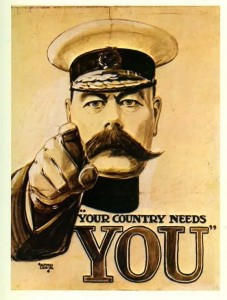

Thankfully, one very important individual had the foresight to perceive that the war was likely to become a much longer struggle. Field Marshal Lord Kitchener was Britain’s most famous soldier, and upon war being declared was appointed Secretary of State for War. Despite the county’s long history of avoiding committing armies to fight enemies on the European mainland, the Government decided that this time, it would be different. Kitchener therefore set about expanding the tiny, but professional and highly trained pre-war army, and creating a vast army that would be able to match that of Germany, and our ally, France.

Many well meaning leaders, such as Mayors and Members of Parliament, took it upon themselves to help the recruiting effort. There had already been a massive response to Kitchener’s appeal, and not all the volunteers could be accommodated in the army. Because of this, an arrangement was made whereby the government allowed the creation of locally raised units, and undertook to reimburse the cost of feeding and billeting the men until such time as the army was able to take over responsibility for them. Many of these locally raised units – better known as Pals Battalions – were raised up and down the country, but this was overwhelmingly a northern phenomenon, with many units being raised in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

One of the Pals battalions was raised in Bradford by a leading citizen, Sir W.E.B. Priestly. After permission was granted by the War Office, recruiting for the battalion started in earnest in September 1914.

Possibly swept up in the excitement of the moment, Malcolm responded to Kitchener’s appeal and joined up. As mentioned above, we can surmise that Malcolm was patriotic, as he was an early volunteer, for the Bradford Pals – we know he was one of the first to volunteer because he was given a low regimental number, being 687. On Friday the 6th November, 1914, the Bradford Daily Telegraph, as part of its “War Relief Fund” campaign, listed the first 1000 men to enlist (along with their trades and professions). Malcolm was one of those listed.

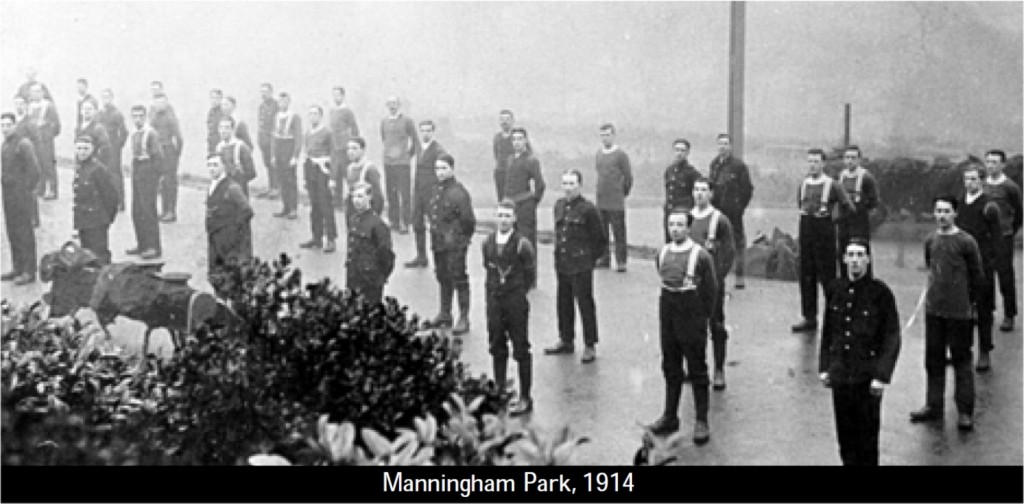

With its Headquarters at the skating rink on Manningham Lane, the battalion’s recruits were drilled in local parks, such as the nearby Lister Park. The recruits were allowed home every evening to sleep, for which the family received an allowance of 21 shillings a week. On top of this each private received pay of seven shillings a week. Due to a lack of uniforms, the men initially wore their own (civilian) clothes, but with Bradford being a major centre of the woollen trade, it was not long before some uniforms – albeit blue not khaki – were made available. Having some (obsolete) rifles and a uniform would have enabled further recruits to be tempted to join up, as described by George Morgan …

Play Clip

George Morgan became a Sergeant in ‘B’ Company, of the Bradford Pals. This audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip 3] – see web site: http://www.bradlibs.com/bradfordpals/index.htm Despite their being the “dandies” it was not long before army discipline started to be felt by the raw recruits, as training was commenced. Play ClipThis recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip10]

The Bradford Pals formed part of the 31st Division, which was made up of ‘pals’ battalions from the north of England, the vast majority being battalions from Yorkshire. As well as Malcolm’s battalion of Bradford Pals, there was a second battalion raised in that city, as well as battalions from Leeds, Sheffield, Barnsley (two battalions), Durham, Accrington and Hull (four battalions). There was even a battalion of miners raised by the West Yorkshire Coal Owners Association. Training continued, but after a few months, much to everyone’s surprise, rather than being sent to France, Malcolm’s battalion, along with others in the 31st Division, was sent to Egypt.

Play Clip

This recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip13] The Bradford Pals, with the rest of the 31st Division, was in Egypt from Christmas 1915 until the end of February 1916, when they were ordered to France – little did they know that they were destined to take part in “The Big Push”, as the anticipated battle was called. After disembarking at Marseilles, the various units were loaded on to trains, the men being crammed into cattle trucks, as described in this next clip… Play ClipThis recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip18]

The Bradford Pals were introduced to the trenches for training purposes, but inevitably started incurring casualties, as described in this next clip…

Play Clip

This recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip20] By mid-June, battle training was undertaken a few miles to the rear at the town of Doullens. George Morgan describes this period… Play ClipThis audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service

For seven days before the assault, the British artillery bombarded the German trenches in the expectation that this would totally destroy all German opposition when it was time to go ‘over the top’. The barrage is described by this Bradford Pal…

Play Clip

This recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip19] The attack was to be made on 1 July 1916. Rather than attacking at dawn, the assault was made at 7.30am, well after the sun had risen. This was not the only problem faced by the British Infantry. Because it was fully expected that the Germans would launch counter attacks, and because of the difficulty in re-supplying troops, the men in the first waves would have to carry all they needed with then. Again George Morgan describes this “kit” issue, as well as the time of the attack… Play ClipThis audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service

As the hours and then minutes elapsed before the attack went in, men had time for their thoughts. George Morgan describes the thoughts that were going through his mind…

Play Clip

This audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service Despite his fears, George was determined to do his best when the moment came… Play ClipThis audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service

At 7.30 the attack was launched, and all along the line men clambered up ladders, out of the trenches and into No Man’s Land

Play Clip

This audio clip is extracted from an interview with Malcolm Brown in 1976 and is courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service The British barrage unfortunately failed to destroy the German artillery, which fell on the men as they made the attack. The German barrage was not the only problem; German machine gunners came out of their deep dugouts – these dugouts were deep enough to be secure against everything other than a direct hit by the heaviest artillery shell. As soon as the machine guns were set up in the remains of the German trenches, they started shooting down the lines of British Infantry as they crossed No Man’s Land. The following clip describes the attack… Play ClipThis recording was made in the 1980s by the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit (BHRU) and is again reproduced by courtesy of Bradford Libraries, Archives & Information Service [clip25]

Despite an extensive search in the Bradford Newspapers, no obituary notice has been found relating to Malcolm Paterson. Even if such an article turned up, it is highly unlikely this would contain accurate information about Malcolm’s last moment. It is by no means certain, but on the balance of probabilities, he would have been killed in No Man’s Land. On the day of his death, Malcolm was just short of 23 years old.

The attack by the 31st Division on the village of Serre was a total failure and casualties were very heavy. The two battalions of Bradford Pals were hit very hard, 1bttn 140; 2nd 93 fatalities.

The Battle of the Somme still attracts a great deal of public interest. Ninety years on from the battle, the BBC’s ran a story about the Bradford Pals attack on 1 July 1916 on their web-site.

Malcolm Paterson lies buried in grave B.16 of the Railway Hollow Cemetery, Hebuterne, a photograph of which is shown at the top of this web page. He is one of just 65 identified casualties at this site.

Name: PATERSON

Initials: M B

Nationality: United Kingdom

Rank: Private

Regiment/Service: West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Own)

Unit Text: 16th Bn.

Age: 23

Date of Death: 01/07/1916

Service No: 16/687

Additional information: Son of Mr. and Mrs. Malcolm Paterson, of West Point, Shipley, Yorks.

Casualty Type: Commonwealth War Dead

Grave/Memorial Reference: B. 16.

Cemetery: RAILWAY HOLLOW CEMETERY, HEBUTERNE

Header Image: The Railway Hollow Cemetary at Hébuterne lies near to the village of Hébuterne in the Pas-de-Calais. The village lay practically on the front line from March 1915 through to the summer of 1918. This poignant memorial contains the remains of 2 French and 107 British soldiers, of whom 44 are unidentified. Those buried here died in three actions on the Somme battlefields: 1st July 1916 (this included MB Paterson), 13th November 1916, and 5th February 1917. Malcolm Paterson's grave is numbered B.16. Family collection.